When the science of arranging personal archives becomes a fine art.

One of the principles archivists in the United Kingdom live by is ‘original order’: keeping archives, as far as possible, in the arrangement in which their creator intended. But in the case of personal papers this is often easier said than done.

The papers of Arthur Salter, 1st Baron Salter, the Conservative politician, civil servant, and academic, were deposited at the Archives Centre by his biographer, Sidney Aster, in 2014. The personal archive which Lord Salter himself had accumulated was unfortunately lost while in storage following his death during the 1970s, and so Professor Aster, in collaboration with Salter’s former colleagues, began collecting original documents and copies of Salter’s surviving correspondence and other biographical material. Aster – who in an earlier phase of his career had been principal research assistant to Churchill’s official biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert – arranged this material, along with his own correspondence, into separate series and posted an inventory of the ‘Salter papers’ on his personal website, but the archive remained closed until his own biography of Lord Salter was published.

Since the days of its first custodian Stephen Roskill in the 1960s, the Archives Centre has made accessible a number of these archives of original materials collected by biographers, which often prove an invaluable source in their own right to future generations of researchers – see for instance the Donovan Papers and the McLachlan-Beesly Papers.

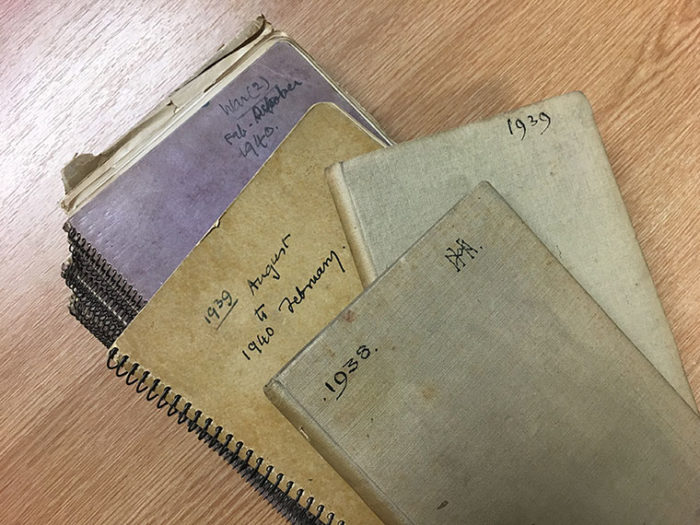

The Hamilton diaries before re-packaging.

Archival processing of Aster’s deposit of Lord Salter’s surviving papers began in earnest in late 2017, but one box of Salter-related materials posed some difficult questions. In the course of corresponding with Salter’s close friends and associates in the British civil service, Aster had made contact with the descendants of Mary Agnes Hamilton (1882-1966), the writer, early woman Labour politician, and public servant. A set of Hamilton’s surviving diaries dating from 1938-1945, which had never been made publicly accessible, contained valuable contextual information about Lord Salter and his partner Ethel Bullard. Aster secured the temporary loan of the diaries for his Salter biography project in 1979, with a view to having them microfilmed and returned to the family – but they were included in his inventory of the collection and the deposit of Salter papers which arrived at the Archives Centre in 2014. A file of correspondence between Aster and Mary Agnes Hamilton’s niece and nephew, including information about the temporary loan of the material, is open in the Salter papers (within series SALT 7, not yet online as it is still being processed). Our first priority was to re-establish contact with Mary Agnes Hamilton’s last surviving descendant, who fortunately was happy for the set of her diaries to remain at the Archives Centre and be made available to researchers.

Archivists have a number of options in this situation. Some might argue that it would be most appropriate to leave Mary Agnes Hamilton’s diaries as they were ‘found’ when they arrived at the Archives Centre, and to treat them as a distinct sub-collection in their original order within the ‘Salter papers’. After all, this collection would not have been assembled in this way at all were it not for the efforts of Lord Salter’s biographer. In conventional archival terminology, however, this would practically be treated as a ‘sub-fonds’ within the Salter papers or a ‘Salter Associated’ collection, and so the author of the diaries would not receive a named entry in our Full Guide, nor the list of the Archive Centre’s individual collections on Cambridge’s networked archives catalogue, ArchiveSearch. Future researchers looking for the personal papers of Mary Agnes Hamilton via search engines (or their equivalents!) would then either have to find their way through the catalogue of the Salter family archive first, or they would need to rely on the presence of an archivist’s note or administrative history in order to work out how another person’s diaries related to Lord Salter’s papers. Any future accessions to these collections-within-collections present a similar set of problems.

Archival description, then, matters a great deal. Strictly speaking, the idea of the ‘fonds’ and ‘sub-fonds’ and other principles of archive administration in Europe originated in the nineteenth- and early-twentieth century management of the records of governments and other institutions.[1] Modern personal papers, whether accumulated within families or deliberately assembled by archives and special collections repositories, bear more resemblance to consciously-created collections, and so the archival profession has started to develop different ways of dealing with them. Indeed, a former Churchill Archives Assistant has studied the issue of multiple provenances for a survey published in the UK Society of Archivists’ journal, which features interviews with current members of the Archives Centre team discussing some of the pitfalls of the historic composite collections here in Cambridge.[2] These decisions are especially important for women – typically under-represented in archives like this one, which was founded to collect the papers of those who have played a ‘prominent role in British public life in the fields most closely associated with Sir Winston Churchill’.[3]

Loose newspaper clipping from 1943 diary, with press image of Mary Agnes Hamilton at the Waldorf Astoria, New York City, for the New York Herald Tribune’s 11th ‘Forum on Current Problems’: a conference to discuss ‘Our Fight for Survival in a Free World’ (16-17 November 1942). No diary dating from Hamilton’s tour to the United States in November 1942 survives in the collection [Archive reference: HMTN 1/9]

The challenges arising from the arrangement of just one box of personal papers show in miniature how all archives have layered and complicated histories – not least the story of how certain documents belonging to certain individuals came to be ‘archives’ in the first place. Personal papers may contain evidence of transactions between individuals and the state or corporations, but as ‘creations of the self’ they also derive much of their value from narrative and tone, from the insights they reveal into character and personality, inner lives and psychologies; traces of recorded memories, relationships, compromises and contradictions; opinions and emotions: in other words, from what they tell us about what makes us human.[4] Even collections ‘self-created’ by one particular individual may contain papers relating to the personal lives of other people.

Twenty-first-century archivists have a duty to make the documentary heritage in their care accessible to society as a whole (even if, as the Thatcher Archivist regularly likes to remind us, there is no such thing …). They can no longer remain bound by the narrow speculations about the contemporary or presumed future research interests of academic historians or biographers alone, which inevitably draw attention to partial aspects of an individual’s life and work at the expense of others. Mary Agnes Hamilton’s association with Lord Salter and his partner Ethel Bullard (with whom she had been at university) in the 1930s and 40s is certainly an important aspect of her life during the period covered by the deposited diaries, and one which will undoubtedly be of interest to other Lord Salter biographers as well as historians of the League of Nations and post-war reconstruction.

On the other hand, Mary Agnes Hamilton herself is also now of great importance to historians of the British left, as an early woman Labour MP (though the diaries themselves date from after Hamilton had left parliament). Any of her surviving papers, previously thought to have been lost, will be of interest to scholars of women’s studies and gender history, while aspects of her life and career during the 1930s and 40s have relevance for the histories of Oxbridge graduates, the life histories of women’s suffrage campaigners, pacifism, journalism and intellectual life, broadcasting and BBC governance, the Ministry of Information, the public reception of the Beveridge Report and the welfare state, Anglo-American relations, and the civil service. And of course, there are bound to be future research interests as yet undreamt of. The trick is representing all of this complexity clearly within an archive catalogue.

If the archivist cannot but fail to be ‘objective’ , then their ultimate aim is to recognize, document, and make their subjective decisions accountable.[5] Judged in terms of the evidence they contain and represent, we reached the conclusion that the diaries far exceed the Salter-Aster connection, but cannot be separated from it. As diaries, however, they were created as a personal record of one individual’s private and professional life, as well as those of the people with whom she came into contact, before and during the Second World War.[6]

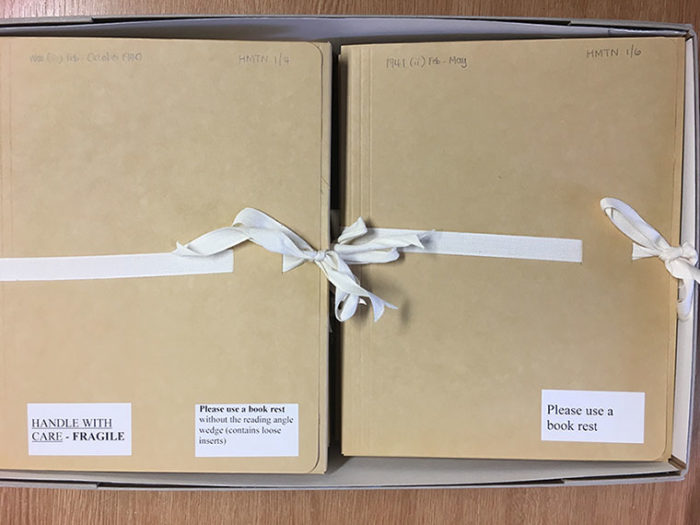

The diaries after being re-packaged in archival grade folders and prepared for use in the reading rooms.

With this in mind and with the approval of her last surviving descendant, we therefore took the decision to assign a separate fonds and collection code – and, with it, a new physical location within the archives – to Mary Agnes Hamilton’s diaries. We have also included a note at both collection and series level to the file of open correspondence relating to the original loan of the diaries in the Salter family archive, so that researchers are aware of this link and the collection’s provenance – should they wish to know more – wherever they may land on the online catalogue.

A minor distinction, perhaps – but one that ultimately makes the difference between a woman’s papers becoming a footnote in another person’s biography and having a collection of their own.

— Heidi Egginton, Archives Assistant

Catalogue to the Hamilton diaries

[1] The French term ‘fonds’ can also be used to describe the ocean floor. See: Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archive, trans. Thomas Scott-Railton (Yale University Press, 2013), p. 131.

[2] Elizabeth Wells, ‘Related Materials: The Arrangement and Description of Family Papers’, Journal of the Society of Archivists, 33 (2012): 167-84. See especially the comments by Sophie Bridges and Katharine Thomson, quoted on pp. 175-76.

[3] The first woman to receive her own collection (Accession number 68), in December 1968, was [Helen Cam link: Helen Cam, Vice-Mistress of Girton College and the first woman professor in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard, followed by Professor Lise Meitner, the pioneering Austrian nuclear physicist who had settled in Cambridge, in April 1969.

[4] Catherine Hobbs, ‘The Character of Personal Archives: Reflections on the Value of Records of Individuals’, Archivaria, 52 (2001): 126-35, at 131.

[5] Terry Cook, We Are What We Keep, We Keep What We Are: Archival Appraisal Past, Present, and Future’, Journal of the Society of Archivists, 32 (2011): 173-89, at 178.

[6] For an excellent history of diary-keeping and diaries as documents in this period, see: Joe Moran, ‘Private Lives, Public Histories: The Diary in Twentieth-Century Britain’, Journal of British Studies, 54 (2015): 138-62.