By-Fellowship report by Dr Richard Johnson, Senior Lecturer in Politics, Queen Mary University of London

In 2021, I was given a grant from Brexit Central to fund research into the history of Labour Euroscepticism. This grant has since supported research publications about Labour’s switch to a pro-European policy in the 1980s and the transformation of Labour MEPs from staunch Eurosceptics to Europhiles. My main objective with this grant has been to write a comprehensive history of Euroscepticism in the Labour Party from Attlee to Starmer. A term at Churchill College (Michaelmas 2022), thanks to an Archives By-Fellowship, has made this book project a closer reality.

At Churchill, I examined hundreds of documents across nine archival collections, mostly belonging to Labour politicians, that shed light on the arguments made against Britain’s membership in the EEC/EU from a Labour Party perspective.

The 1945-51 Labour government rejected plans to join a project of European unity over concerns about democratic decision-making and national economic planning. From those early days, I examined the papers of Ernest Bevin, Attlee’s Foreign Secretary. Bevin famously ‘empty chaired’ the Schuman Plan conference in Paris, which set the stage for the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community.

Although as a younger man Bevin had been an idealist about European unity, his experience of the war convinced him that a political project in which Germany would have a decisive influence over policies in Britain was not something he could stomach. He described his shift in vivid terms at a 1947 Transport and General Workers’ Union conference:

‘I hear talk of the United States of Europe. Well, I moved a resolution on that, Mr. Chairman, myself twenty years ago at the Trades Union Congress at Edinburgh, and Mr. Churchill must have picked up a leaf out of the report. (Laughter) We were talking in a different world then… You go to a country where 5 million of the population have been put through an incinerator – burnt. It is not much good talking to them about being good neighbours with the fellow who did it. It is not, really… You cannot say to a man who has been forced, with the threat of the concentration camp and the whip and all of the rest of it, “Go and fall on the other chap’s neck next morning. Be a good fellow.” It does not work’. (BEVN II/5/8)

From the 1940s until the late 1980s, with brief exceptions, the majority view within the Labour Party was against joining (and, then, in favour of leaving) the European Economic Community (EEC). Even in the 1975 referendum, the official Labour Party position was to support the No (Leave) position. John Silkin, a minister in the Wilson and Callaghan governments, articulated the traditional left-wing concern about the power of judges overriding the decisions of national parliaments. In a 1979 speech at Newcastle University, Silkin explained:

‘I have never understood why we accepted the jurisdiction of the European Court in the first place. Its decisions override the highest courts in our country and there is no appeal from it. It cannot be called a Court of Justice in the usual meaning of the world. It is a political court designed to destroy the national position of any individual member of the EEC if that country is in a minority’. (SLKN/8/2/2)

The most extensive and revealing collection was the Kinnock papers, a great treasure trove in the Churchill Archives. Among its many insights, the collection revealed a significant lobbying effort by Labour MPs to persuade Kinnock against a fulsome embrace of the EEC. For the first five years of Kinnock’s leadership, the Labour Party’s official policy was to withdraw from the EEC if significant reforms were not undertaken. However, efforts by Kinnock, his Policy Review, and the European Commission President Jacques Delors led to Labour to abandon its ‘leave’ position in late 1988.

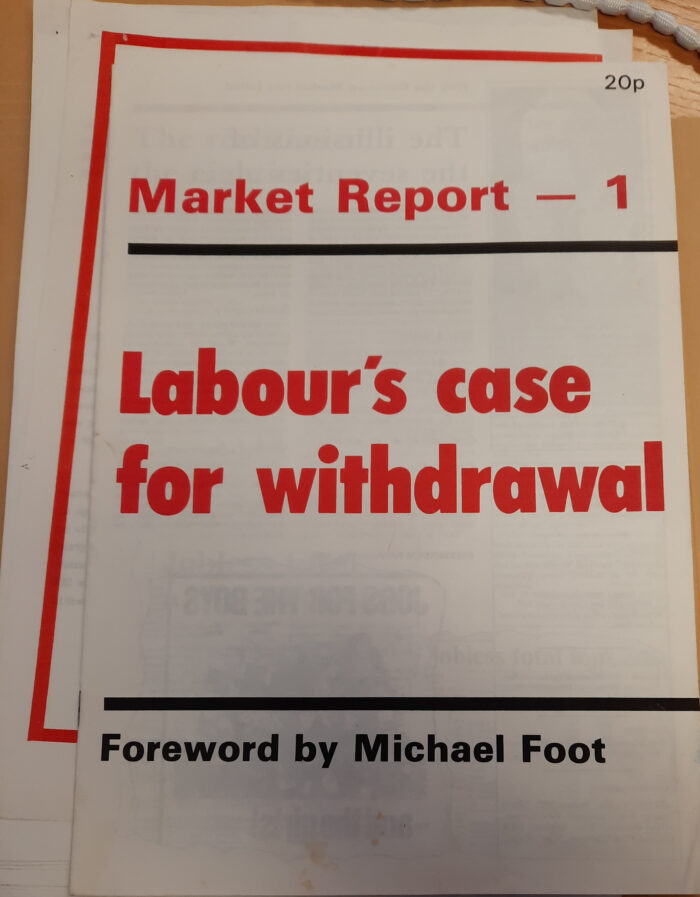

Various Labour MPs were not fully sold on the conversion. Former Labour leader Michael Foot privately told Kinnock that his position ‘concedes much too much to the pro-market case… The question of the sovereign, parliamentary control over these issues still remains of major importance’ (KNNK/1/323). David Blunkett, later a Cabinet minister under Tony Blair, warned Kinnock that ‘social Europe’ might well be a mirage and that a much more ‘realistic’ impact of the Single Market would be to advance right-wing goals (KNNK/1/3/23).

Perhaps the most interesting find from the Kinnock collection were notes from a meeting in 1989 in which Kinnock encouraged Delors to emphasise to French President François Mitterrand ‘how critical it was to isolate Thatcher’. Kinnock told Delors, ‘She deserves to be isolated for she is disadvantaging Britain, there is no point doing any deal with her’ (KNNK/8/36). These exchanges demonstrate how by this stage Kinnock – and many others in Labour — believed the EEC/EU could be used to undermine the Conservative government back home.

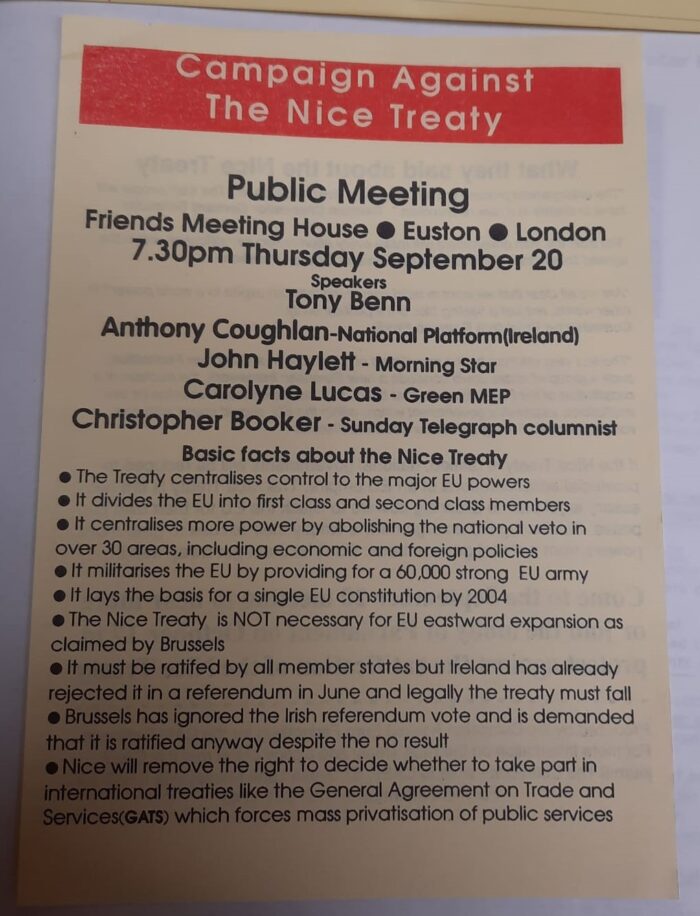

Not everyone embraced Labour’s conversion to Europe in the late 1980s. Nigel Spearing, a London MP from 1970-1997, was a dedicated member of the Labour Common Market Safeguards Committee. Spearing’s collection is itself a kind of personal archive of the Labour Eurosceptic movement from the 1970s right up to the 2016 referendum (Spearing voted Leave before his death in 2017). The movement’s de facto leader Peter Shore features prominently in the collection, with Shore bemoaning the rise of the ‘implausible coalition of old Tory and New Labour’ over Europe (SPRG/2/5).

Another figure who retained his Eurosceptic views after Labour’s conversion was Peter Jay, son-in-law of the Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan who had appointed Jay as Ambassador to the United States. In the 1990s, Jay condemned Labour’s embrace of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), predicting (accurately) it would lead to disaster and an abandonment of Labour’s socialist political economy:

‘The Labour Party, if you read Neil Kinnock’s lecture on 28th February of this year [1991] to the Institute of Public Policy Research, I mean it is amazing. I mean every single policy which any government has ever followed since the war has been thrown out. I mean no planning, no nationalisation, no demand management, no exchange rate flexibility or changeability, no incomes policy. But in addition, he’s absolutely committed not merely to one monetary straitjacket but to both – he wants both a fixed exchange rate and monetary aggregates.’ (PJAY 5/4/6)/

I also examined some of the papers of those who disagreed with the Labour Eurosceptics. These included the Labour Europhiles Tam Dalyell and Michael Stewart, as well as the Conservative Eurosceptic Enoch Powell and Conservative Europhile Christopher Soames (whose collection includes a letter to Ted Heath vowing to ‘stamp hard on Shore soon by some means or other’ (SOAM 3/2/1)).

Perhaps one of the most intriguing findings of my stay was a letter from Dipak Nandy, father of the frontbench Labour MP Lisa Nandy, to Enoch Powell. Nandy had been Director of the Runnymede Trust and was closely associated with fighting for racial equality in Britain. Yet, Nandy wrote to Powell to say how sad he was that Powell did not stand for re-election in February 1974. Nandy urged Powell not to withdraw from public affairs, even if they held different views on race and immigration. Nandy also praised Powell for insisting that the public have a say over EEC membership. (POLL/1/22)

Thanks to the friendly and helpful Archives staff as well as the broader fellowship of Churchill College, my months as a by-fellow proved not only intellectually stimulating and productive but also enjoyable and socially enriching.

Dr Richard Johnson