Recovering the Useful Past: Naval Historians at the Fore

It is often overlooked that naval historians have been at the forefront of developing not just sub-fields to the discipline of the study of history (such as military history) but also supporting the critical foundations in which to support its advancement. The actions of these historians included supporting the creation of places that could hold and protect original documentary evidence for future generations to study, such as Churchill Archives Centre.

Photograph of Stephen Roskill from the Fellows’ Album, c. 1961, Churchill College Archives CCPH/1/6

Luminaries like naval officer Stephen Roskill (1903-1982) worked tirelessly in the post-Second World War decades alongside Sir John (“Jock”) Colville (1915-1987) and Sir John Cockcroft (1897-1967) to seek deposits and expand collections for Churchill Archives Centre. These were not to supplant collections held in national repositories but to complement them as was occurring elsewhere, such as at the National Maritime Museum.

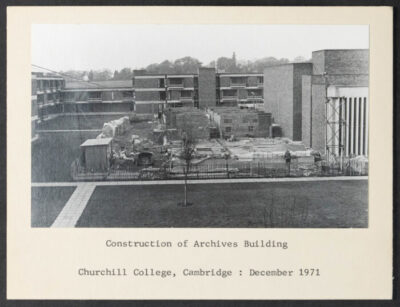

Photograph of a card sent to the Roskills at Christmas

From the Papers of Stephen Roskill, ROSK 18/7

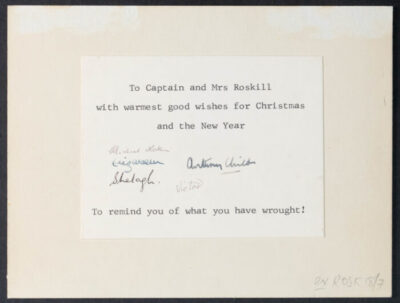

A leaflet from the opening of Churchill Archives Centre in 1973. From the papers of Stephen Roskill, ROSK 18/7

Roskill was part of a line of British military historians that had started in the 19th century when Sir John Knox Laughton (1830-1915) (another former naval officer) joined the History Department at King’s College London. Laughton underlined that military history, which was poorly recorded at that point in time, was more than just a collection of mythic battles, honourable deeds, and distant glorious campaigns. There was something valuable to be recovered from experience not just for the military but for policy and high-level decision-makers. Laughton inspired strategists such as naval historian and philosopher of seapower Sir Julian Corbett (1854-1922), who understood that developing coherent contemporary national strategy and government policy lay in the sustained study and analysis of history.

Laughton, Corbett, and Roskill understood that the labyrinth of dry reams of pages of official government documents and records held in national archives only painted part of a picture. They knew equally useful insight could be gained from personal and private records beyond the black-and-white of official government policy and business. The process of how something got from ‘A to B to C’ and trends over time was as study worthy as the outcome, nor was it wise to ignore the personalities, influences, interactions, and culture–the human element that reflected the times they lived–from research.

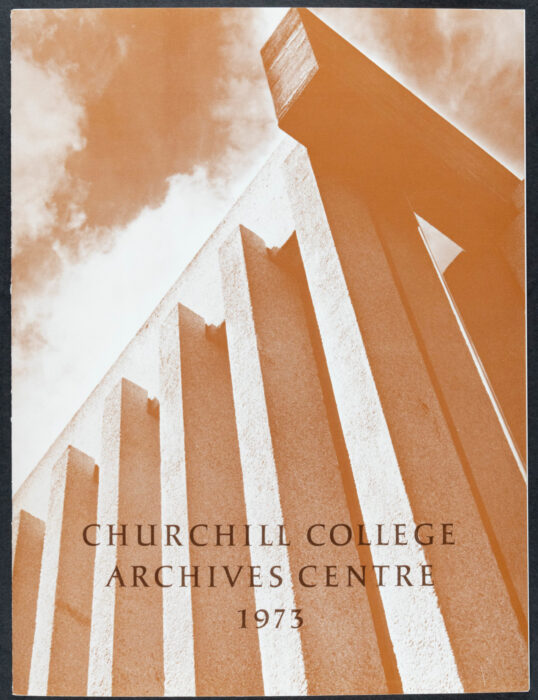

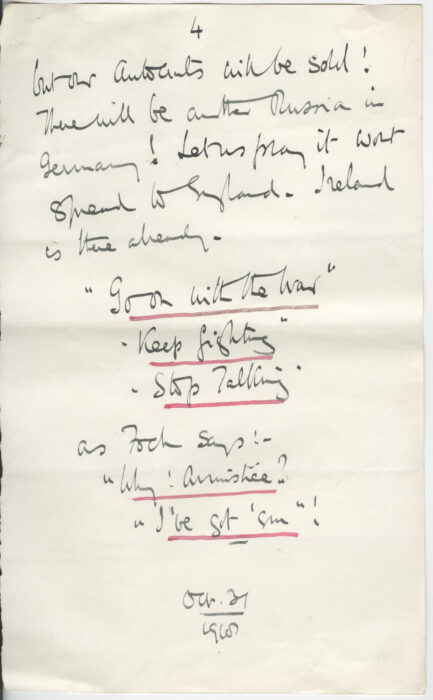

First and last page of a letter from Admiral Lord John “Jackie” Fisher to written to George Lambert on 31 Oct 1918, arguing against an armistice with Germany. Reference: FISR 16/5.

The Fisher papers came to Churchill Archives Centre in 1980.

Naval historians were central to efforts to push forward the creation of new archives, expand collections and build museums in the United Kingdom and abroad, such as in the United States. They worked with other historians and the military, mindful that future students and researchers should not constrain themselves just to national archives. Instead, they should deepen their understanding by using all the tools and resources available as they seek to answer questions by also using the rich documentary evidence held in places such as Churchill College. They believed that experience (the past) is all we have freely available to harness guidance from, rather than running the tightrope of relearning the costly and hard way, with all the risks associated with it, whether that be in government policy or military decision-making.

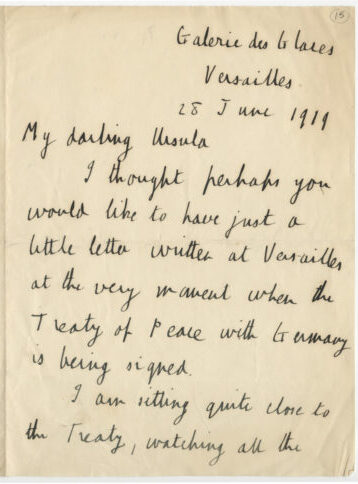

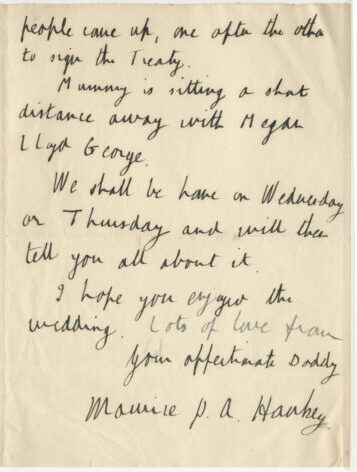

Letter from Maurice Hankey to his daughter Ursula written during the signing of the Paris Peace Treaty. Reference: HNKY 4/11/15.

The Hankey papers were deposited at Churchill College in 1967, and Stephen Roskill wrote the official biography of Hankey (‘Hankey: Man of Secrets’) which came out in three volumes between 1970 and 1974.

Naval and maritime history as a field after the 1960s could only secure a niche following compared to the boom in interest in military history. This reflected the reality of the rejection of Britain’s normative maritime strategic culture, which Corbett had studied and subsequently worked to educate the military and politicians about earlier in the 20th century. However, as a field, its roots remained dedicated to the fact that there was something worthwhile to recover from the useful past to inform the challenges of today and tackle the questions of tomorrow. This occurred long before military history became a serious academic pursuit when Sir Michael Howard (1922-2019) formed the War Studies Department at King’s College London in the 1960s. Since then and partly due to Roskill, the students and staff of Churchill College, the Churchill Archive Centre and King’s College London have enjoyed a close relationship that remains to this day.

The reading room at Churchill Archives Centre

Dr James W.E. Smith is a Research Fellow in the Department of War Studies, at King’s College London. His PhD ‘Deconstructing the Seapower State: Britain, America and Defence Unification 1945-1964’ (2021) drew significantly from records held at the Churchill Archives Centre, University of Cambridge.