The Churchill Archives Centre is known for holding the papers of post-Second World War figures in politics, science and the military, most of whom were British. Peppered within these papers, however, one sometimes comes across something very different. This blog post explores an item discovered amongst the Papers of Jeremy Bray: a ‘baby weight book’ from 1930s China.

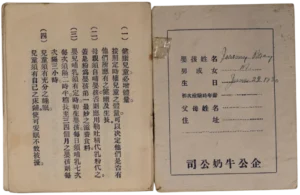

Jeremy Bray was born to missionary parents in British Hong Kong in 1930. He and his siblings Denis, Barbara and Elenor grew up in southern China speaking Cantonese and English. Denis would become Secretary for Home Affairs in the colonial Hong Kong Government (1973-1977 and 1980-1984). Although Jeremy would spend much of his life in Westminster as a Labour Member of Parliament (1962-1970 and 1974-1997), given his upbringing and his family connections to China, it is unsurprising that some Chinese-language items are amongst his papers.

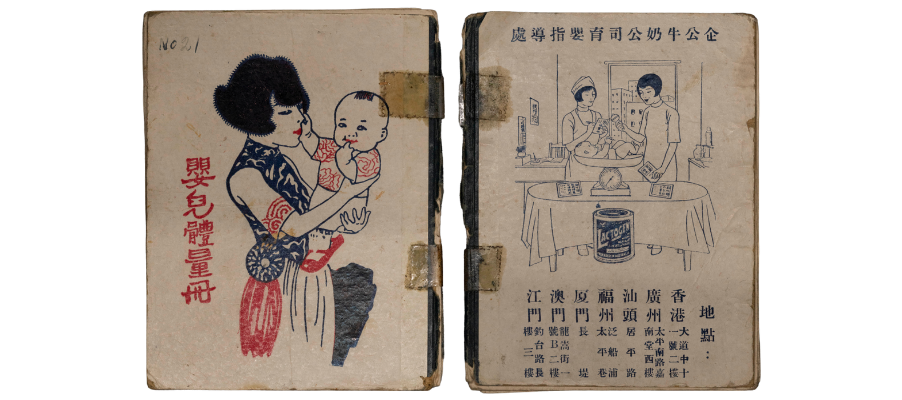

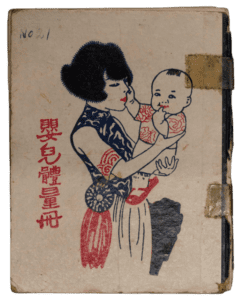

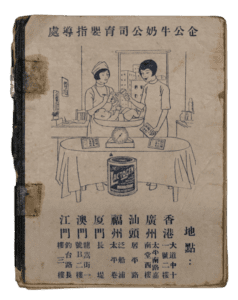

One such item is a palm-sized notebook titled ‘baby weight book’ (Ting’er ti liang ce, 嬰兒體量冊).

It dates from the 1930s – a fascinating decade in China’s history. In the 19th Century, foreign companies and militaries forced their way into China. They carved out enclaves for trade and designated areas as being under extraterritorial law for the comfort of expatriates. The Qing Empire fell in 1912 and was replaced by an uneasy Republic hampered by factionalism and undermined by rampant warlordism. With China weak, foreign forces expanded their footholds in the country. By the 1930s, one could find foreign goods, people and ideas in many Chinese cities.

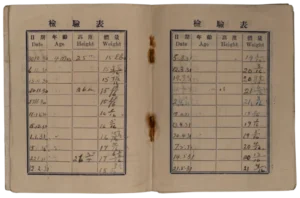

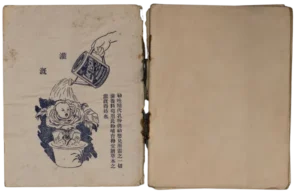

Ostensibly, the baby weight book had a medical purpose: it provided a space for parents to track their baby’s measurements over time. In Making it Count: Statistics and Statecraft in the Early People’s Republic of China, Arunabh Ghosh charts the adoption of statistical methods by successive Chinese governments and shows how ideas about record-keeping from Europe and America were imported into China. The very notion of measuring a baby’s growth using standardised units, represented also by the depiction of weighing scales on the back cover, would have been a fairly new one for 1930s China.

The notebook was also an exercise in advertising and was probably given to parents for free. It features images of the milk powder product Lactogen and the name of its producer, Qigong Milk Company (Qigong Niunai Gongsi, 企公牛奶公司), a Nestlé company, emblazoned on multiple pages. While the notebook itself is bilingual, the text on the depictions of Lactogen cans is only in English and proudly states ‘Prepared in Australia’. This was no mistake: the manufacturers were likely capitalising on the fact that imported goods came with a certain cachet.

In the 1930s, cosmopolitan cities such as Shanghai, Tianjin and Hong Kong (under British colonial administration) mixed foreign fashion, architecture and ideas with the traditional. Out of the window depicted on the back cover, for instance, there are high-rise buildings – associated more with 1930s New York than 1930s China. Also on the back cover, two women sport shingle-style bob haircuts which originated in Europe in the late 19th Century. The presumptive mother on the front cover wears a bouffant, a French pouf-style hairdo. These European imports occasionally intermingle with traditional Chinese styles: the mother figure, for instance, wears a traditional qipao (旗袍) dress with her hair. The medical professionals on the back, meanwhile, wear recognisably medical uniforms which we might associate with sanitation.

Beyond changes to China’s appearance, the notebook also reflects conceptual epochal shifts. In the book Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China, Ruth Rogaski traces the journey of germ theory from Germany to China via Japan and the resulting in revolution in hygiene or weisheng (卫生). We see this reflected in the baby weight book. Several pages list tips for keeping a baby healthy. Tip six (liu, 六), for instance, says that children should be kept separately from ill people as disease can be infectious or contagious (chuanran, 傳染): this would have been a relatively new concept. More broadly, around this time Traditional Chinese Medicine was slowly being replaced by Western medicine, represented by the two uniformed female figures.

The baby weight book was designed to sell milk powder by promoting something far more aspirational: a vision of a modern, scientific form of parenthood where Western concepts and appearances were displacing traditional Chinese ones. From imported hairdos and skyscrapers to changing ideas about sanitation and statistics, the baby weight book is emblematic of 1930s China and its relations with the wider world. While it is perhaps surprising that this object was found in the papers of a British Labour MP, there are doubtlessly many other delights to be discovered amongst the Churchill Archives Centre’s many collections.

— Matthew Hurst, July 2024

The research for this article was supported by WRoCAH as part of the AHRC Researcher Employability Project.

Other news