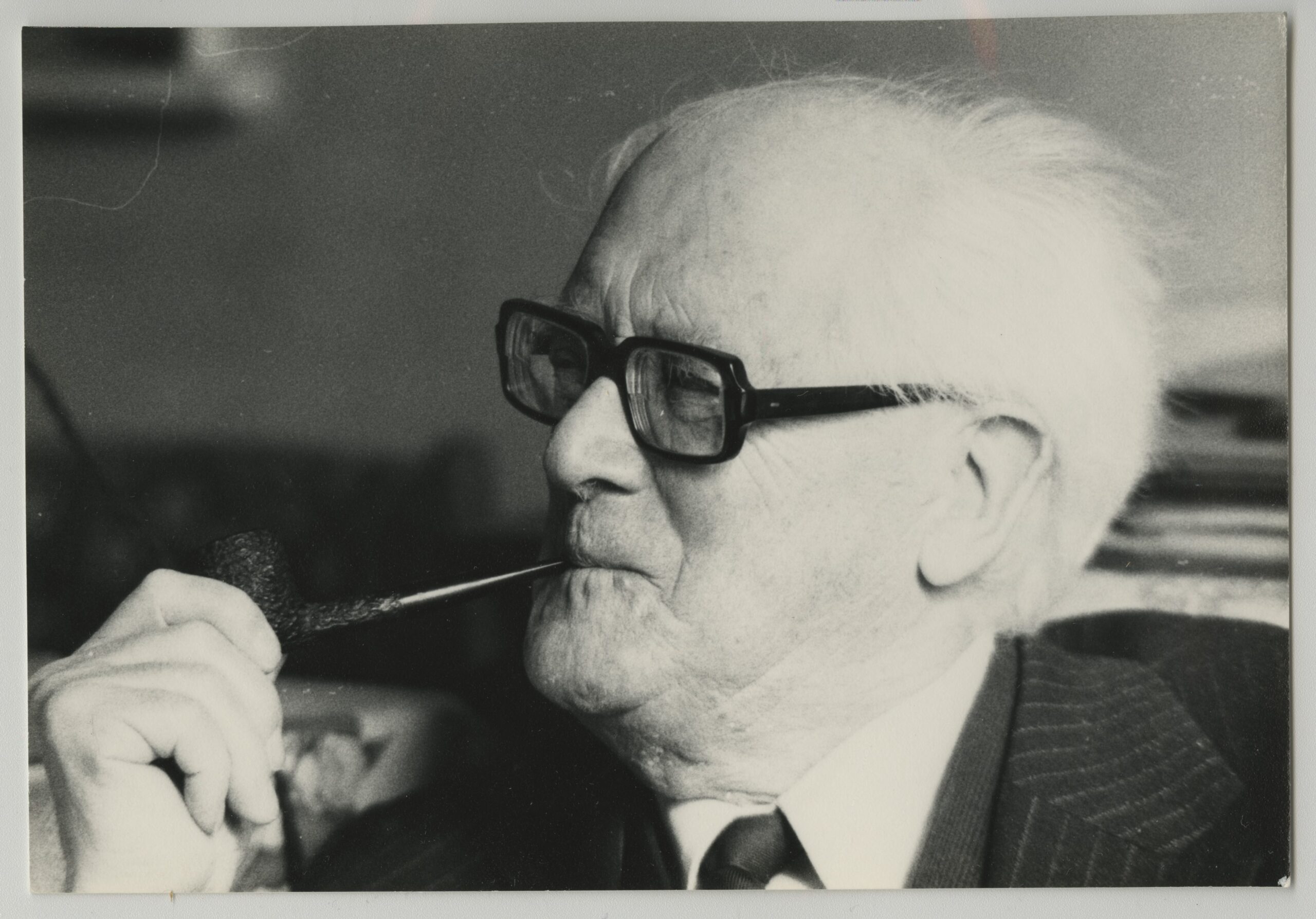

Not that many people these days have heard of Fenner Brockway, but in his time (and it was a long time, as he lived to the age of 99), Brockway was an important figure both in the Labour movement and in the history of campaigning. His fascinating archive, which previously only had a summary list, so was not that easy to use, has now been fully catalogued, making it properly accessible for the first time.

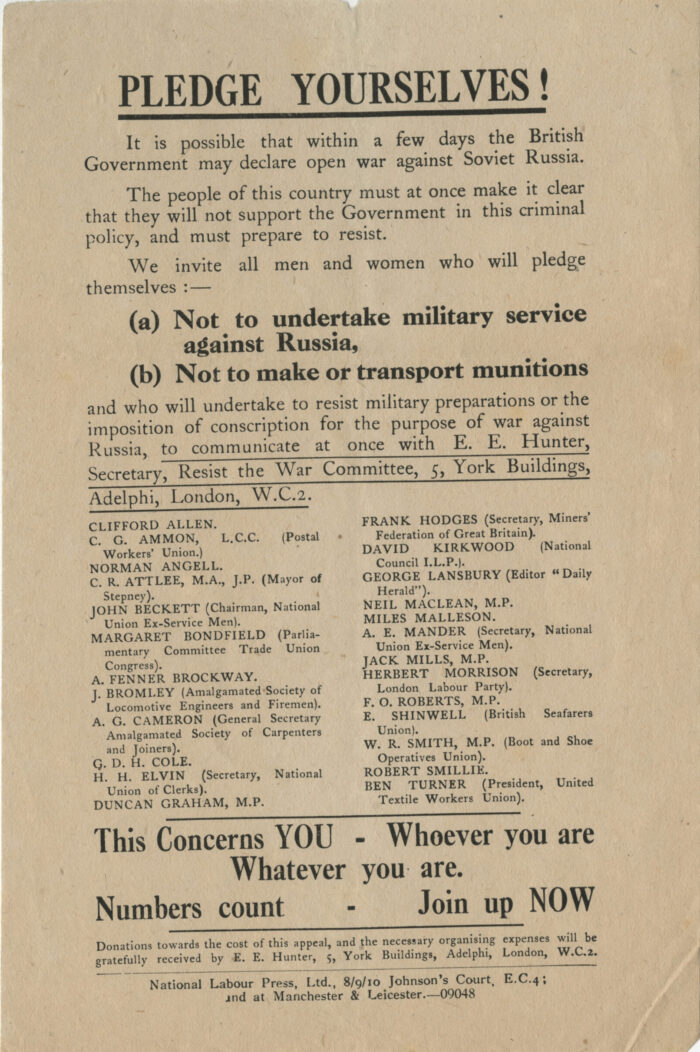

Born to missionary parents in India in 1888, Brockway initially worked as a journalist, and soon joined the Independent Labour Party, editing the ILP journal, the Labour Leader, from 1912-17. For part of this time he was actually working from prison, as during the First World War Brockway served four terms of imprisonment, the last eight months of which were in solitary confinement, as a conscientious objector.

Brockway became a leading light in the ILP and was elected as MP for East Leyton in 1929, but as the ILP moved further and further to the left, away from the official Labour Party, he became an increasingly radical figure, losing his seat in 1931. Under his chairmanship, the ILP finally broke with Labour in 1932, something which Brockway later admitted had been a serious mistake. Observing Communism from close quarters during the Spanish Civil War, Brockway’s radical socialism became a little more pragmatic, while the rise of fascism and the Second World War caused him to modify his views on pacifism, and he returned to the Labour Party in 1945.

Brockway became MP for Eton and Slough in 1950, and while remaining a leading figure on the left, after the war his energies were mainly channelled into campaigning. He had been an early supporter of women’s suffrage; now he became best-known as an anti-colonial activist, or “the member for Africa”. He helped to establish the People’s Congress Against Imperialism in 1948, was a founder and Chairman of the Movement for Colonial Freedom (later Liberation) and worked tirelessly against racism. Brockway’s early pacifism found expression in his support for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and in 1979 he and his fellow octogenarian Philip Noel-Baker founded the World Disarmament Campaign. If anti-colonialism and campaigning for nuclear disarmament were his two main concerns, Brockway also fought on behalf of many other causes, including penal reform and he took a particular interest in prison conditions and civil rights in Northern Ireland during the 1970s. Having lost his Eton and Slough seat by a whisker in the 1964 General Election, he accepted a life peerage (not without some misgivings) and remained a vigorous campaigner from the Labour benches of the House of Lords for the rest of his long life.

Most unfortunately, most of Brockway’s early papers were lost during the war when the ILP headquarters in London were bombed, so that his archive mainly dates from the 1960s onwards, though there is some earlier material, including a fascinating correspondence with his old friend George Bernard Shaw. There is also a whole series on the World Disarmament Campaign and a large literary section, mostly covering Brockway’s 1973 work The Colonial Revolution as well as two autobiographical volumes. Much of the archive, however, consists of Brockway’s political correspondence, which covers an amazingly wide range of issues, but is in particular a splendid source for studies into immigration, race relations, civil rights, prison conditions and former colonial countries during the 1960s-80s.

Katharine Thomson, Archivist, June 2024