What happens when a historical figure you admire goes missing for six months? This is what happened to me with Colonel Ralph Bagnold. Many people know about his desert explorations before the Second World War, and during it as founder and first commander of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG). Less well-known is his later role as Deputy Signals-Officer-in-Chief for the British Army’s Middle East Operations.

But the months between Bagnold handing over the LRDG and taking up his new Signals role are missing completely. Even in Bagnold’s own memoir Sand, Wind and War, they’re a blank. That’s characteristic of Bagnold’s reticence, as, in the book, he scarcely augmented what he’d already been asked to write about the LRDG itself by the War Office. So, what was this quiet, modest but very impressive 45 year old man doing during those critical six months of the Second World War?

Searching through the mountain of literature about The Desert War, I began to see that it was scarcely any wonder why Bagnold passed over that period. He had walked into a hornet’s nest. It was only through being given access to his diary (reference BGND A.26) by the wonderfully supportive team at the Churchill Archives Centre that I began to see what had really happened. The diary, incidentally, shows clearly that Bagnold was devoted to his tasks, loved rock climbing, and enjoyed the company of a wide variety of people including General Edward Spears, Freya Stark and Cecil Beaton. He dined regularly with influential ‘top brass’ and took care to encourage promising young officers. It’s also clear that he handled a six-month long tussle extraordinarily well.

On October the 14th, promoted to colonel, Bagnold was appointed by Brigadier Jock Whiteley to command a new Middle East Camouflage Branch, intended to bring all types of Deception – Camouflage, Visual Deception, Sabotage, Counter-intelligence – under the control of Middle East Operations. In effect, control of tactical planning, camouflage, and production of dummy equipment was being taken away from Intelligence and given to Operations.

For months, there had been tensions between the two departments in Cairo. Dudley Clarke, Head of ‘A’ Force Intelligence had been away since August, and the demand for camouflage training and dummy material for visual deception had shot up, to the point where it had become increasingly clear that Intelligence was unable to carry out all the tasks required, let alone liaise effectively with tactical commanders facing the legendary General Rommel in the field.

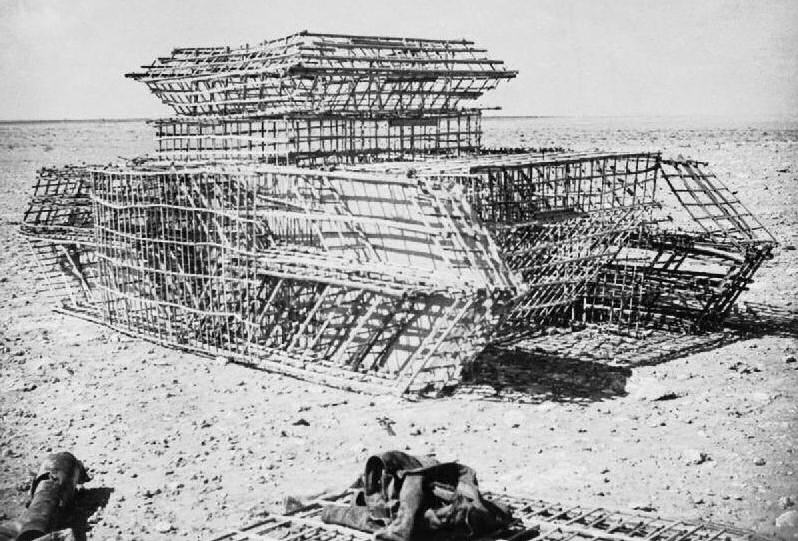

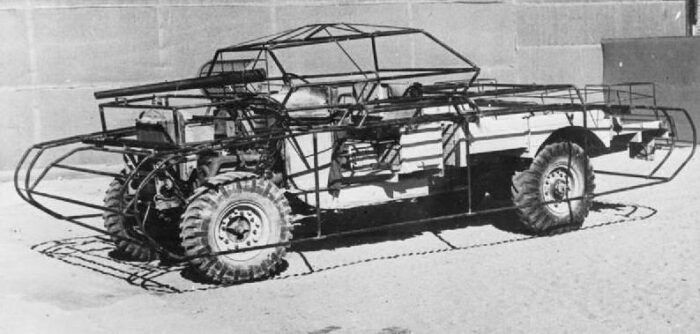

During Ralph Bagnold’s six-month tenure in command of Camouflage and Deception, here is what was achieved: the number of unit personnel tripled, a training centre was set up, production and distribution of dummy tanks, trucks, guns and equipment was streamlined, effective deception plans for General Auchinleck’s next attack were put in place, including a dummy tank regiment and a dummy railway. A dummy port was built, dummy aircraft and airfields were created, and the profile and importance of visual deception as a whole was raised.

On the 8th of March 1942, Bagnold handed back control of Camouflage and Deception to Dudley Clarke. Clarke was unhappy about the branch being under Operations and no longer under Intelligence, and blamed Bagnold for simply doing well what he’d been asked to do. Perhaps it deflected attention away from Clarke’s having been arrested in Madrid in women’s clothing the previous October.

At least four officers involved in visual deception subsequently claimed credit for the ultimate hoodwinking of Rommel before the Battle of El Alamein. None of them had anything pleasant to say – if at all – about Bagnold’s groundwork. Many historians have followed suit. Bagnold characteristically chose not to defend himself. His reputation rests on his explorations, the LRDG, and his subsequent career as a highly-respected geological scientist, but in his diary the facts speak for themselves. Now I know what he did during those missing months.

By Ruary Mackenzie Dodds (researcher and guest blogger)

The views expressed are the views of the writer alone, and are not endorsed or otherwise by Churchill College in any way whatsoever.