Treasure Hunting Part 3: The Unexplored Unconscious of the Churchill era

The theatre work The Miracle haunts the first half of the 20th century. Restaged or re-envisioned with popular and critical success three consecutive decades, its impact on the era remains curiously under-researched. It is as if something about it is important but difficult to talk about. Indeed, one of its key characteristics was its wordlessness. Or maybe something was too close for the comfort of analysis, and thus passed eventually into obscurity.

The work is a modern take on the mystery play tradition. Communicated through movement, music, and staging, a wayward nun is seduced by a knight and evil minstrel to leave her convent. The statue of the Virgin Mary comes to life and takes her place during a journey into the real world. After experiencing hardship and persecution, the nun finally returns to the convent, is forgiven and the Virgin Mary becomes once again a statue.

Its influence began with its hugely successful premiere at London’s Olympia for the Christmas season of 1911 and went on with sell-out performances until the spring of 1912, quite a feat for such a large venue and complicated production which included, among other things, live horses. In 1924, The Miracle was revived in the United States premiering at The Century Theatre in New York featuring the British aristocrat and actress Lady Diana Cooper (featured above) as the Virgin Mary and eventually also the role of the nun. The production greatly surpassed the popularity of the 1911/12 original. It toured to sold out audiences continuously throughout North America for three years, with a visit to selected European cities in the summer of 1926 and the winter of 1927. The work was subsequently restaged in London in 1932. It was, once again, well received with Diana Cooper and Leonid Massine, Tilly Losch and Maud Allan joining the cast. Not as much a blockbuster as its predecessors, it was still enormously popular. Furthermore, while not a direct reproduction, its characterisations and elements of magic realism can also be seen to echo in Robert Helpmann’s popular Sadler’s Wells Ballet Miracle in the Gorbals given at the height of the V-2 bombing of London.

The Centre is a particularly useful repository for information about The Miracle as it holds the voluminous correspondence accrued between Diana Cooper and her husband Duff Cooper while she was performing with The Miracle in America. These are held in the Duff Cooper papers (DUFC) and are reproduced in edited form in A Durable Fire: The Letters of Duff and Diana Cooper 1913-1950 by Artemis Cooper, their granddaughter.

The collection’s material on The Miracle is searchable on the Cambridge University Archives catalogue. But what also makes the Centre’s collection useful and attests to the haunting impact of The Miracle in this era itself are the places where The Miracle pops up unexpectedly.

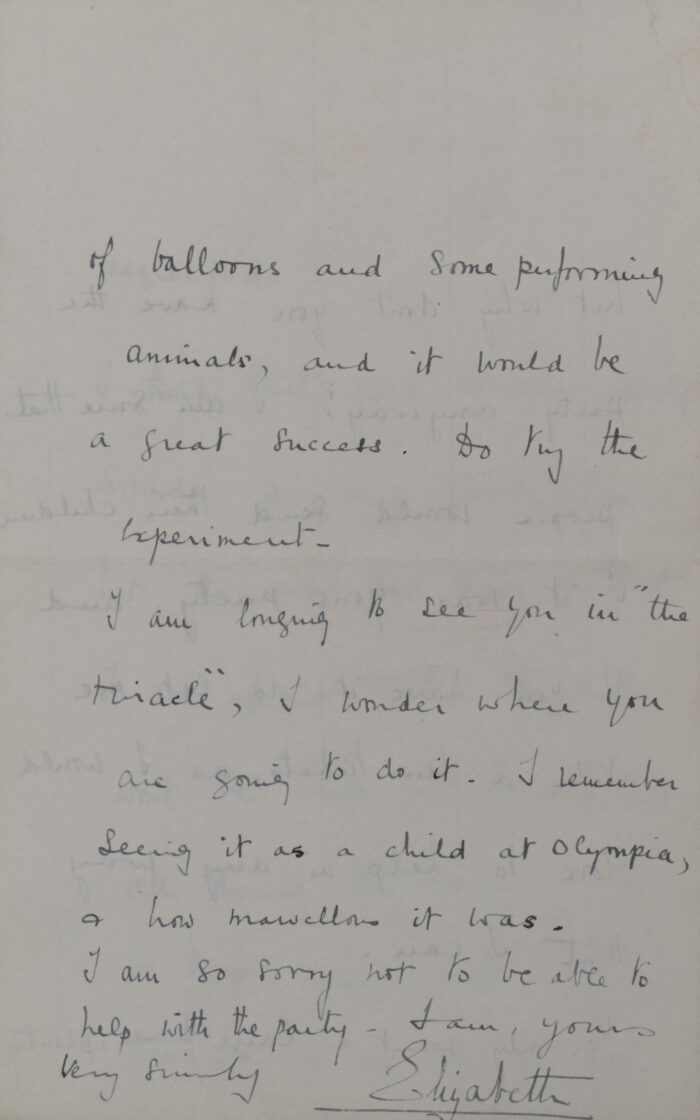

Hidden in Duff Cooper’s papers (DUFC 11/2) is an unexpected letter from Elizabeth, Duchess of York in 1931 (later Queen Elizabeth and Elizabeth, the Queen Mother) to Diana Cooper asking when Cooper would again appear in The Miracle and remembering with fondness the version she saw as a child in 1912 at Olympia.

Letter from Elizabeth, Duchess of York, 8 January 1931 (DUFC 11/2) © His Majesty King Charles III.

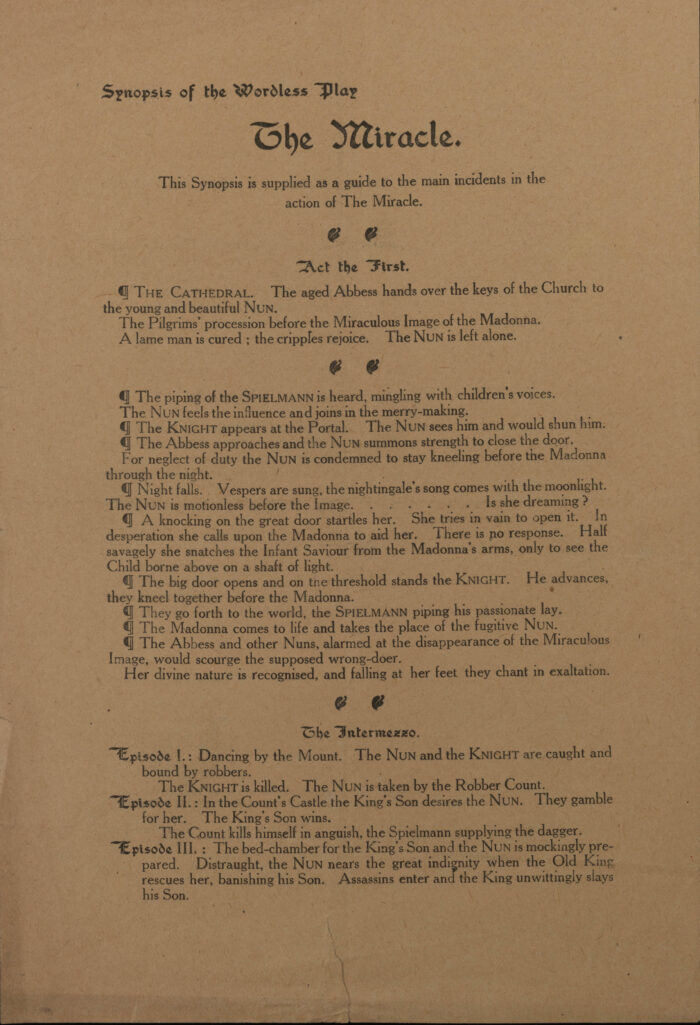

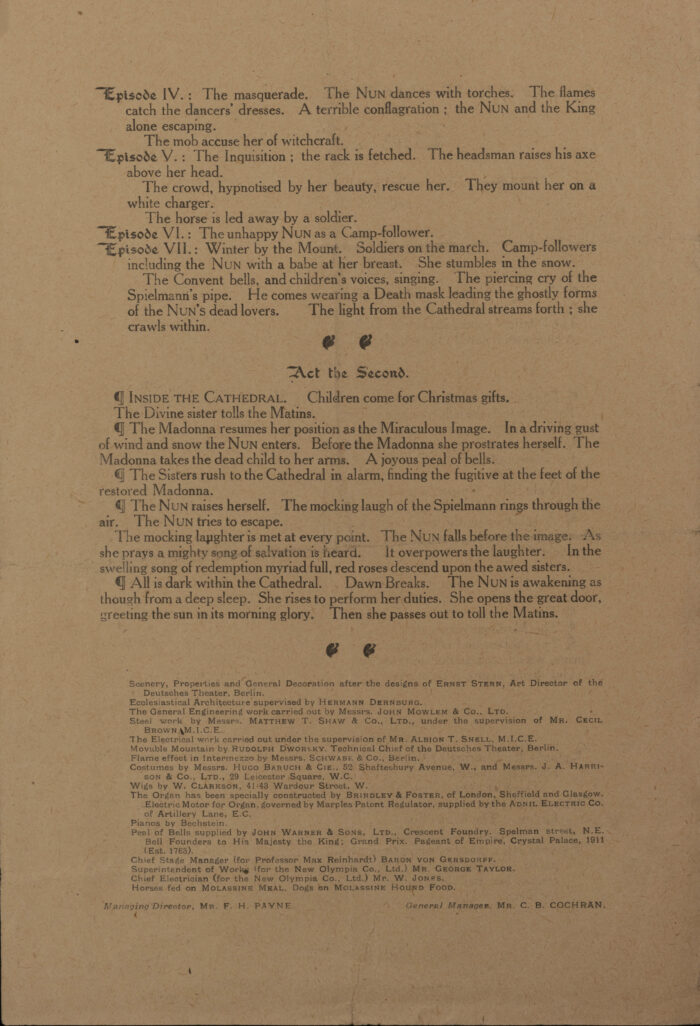

Then, in William Bull’s papers (BULL 4/4), amidst files containing diaries and correspondence is a synopsis for the 1911/12 version of The Miracle.

Synopsis of The Miracle, undated (BULL 4/4).

What is most striking, and attests to the political dimensions of the work, is an interesting passage in one of Diana Cooper’s letters to her husband. She writes,

“Kommer is going to write you a letter about the political aspect of the Miracle in Paris. Don’t listen too much to him because he thinks too precisely on his balancing judgements. It is to be put on at the expense of the German and French governments as a gesture of amity, that of course is a pie I’d like a thumb in. […] It would be only about twice a week, for 3 or 4 weeks – still I told him to write no political cons and anyway I shouldn’t think it would come off” (DUFC 1/14/1)

Written in January of 1927, it comes at the tail end of the prolific touring The Miracle had done since opening in 1924. “Kommer”, who Diana Cooper references, was Rudolf Kommer, a Jewish Ukrainian journalist hired as one of the work’s impresarios and Reinhardt’s US representative. He was a mysterious figure—an excellent producer who contributed to The Miracle’s unprecedented success in the 1920s. Although he supported German Jewish artists in exile, he was still suspected by the FBI of spying for the Axis powers.

From one point of view, the passage illustrates the kind of influence The Miracle enjoyed, where some like Kommer envisioned it as having the potential for political influence, and where different nation-states were willing to pay for its production. Indeed, this interest on the part of Kommer provides a thought-provoking glimpse at his motives for and energy toward the success of the work.

The letter also shines an important light on Diana Cooper herself. First, more generally, she remains an unsung canny political influencer. She was the glamorous presence in Cooper’s various election campaigns. At the same time, she was his financier—her earning from The Miracle allowing Cooper to leave the Foreign Office for a career in politics. In the letter, she shows a wily ability to temper the play between different personalities. “Don’t listen too much to him” is a line possibly motived by an understanding of the Type A personalities of both men, while also supporting the venture without appearing over-enthusiastic – “that of course is a pie I’d like to have a thumb in […] I shouldn’t think it would come off.” This subtlety and persuasion begs for great interest in the political dimensions of her letters.

In sum, The Miracle augurs an exciting new lens for research about the Churchill era.

This blog was written by Dr Victoria Thoms, Associate Professor at the Centre for Dance Research (C-DaRE) Coventry University. Read more about her work in Treasure Hunting Part 1: Confessions of a Dance Scholar and Treasure Hunting Part 2: Sir Alexander Cadogan as Curmudgeonly Ballet Superfan.

This blog is part of our ‘50 stories for 50 years’ series to mark the 50th Anniversary of Churchill Archives Centre.